Dancing with the Gods

The First Movements of Humanity

You think you know dance, but all that you are able to imagine about movement and rhythm pales compared to a world of ancient Egyptian ritual dance that allows significantly new insights into the importance of dance in Egyptian culture. The scene reveals an altogether new emphasis between musical instruments, singing, and dancing, as we will see in the following. In ancient Egypt, dance and cult have been connected since earliest times. Several depictions appear in temples and tombs showing the performance of dance within the context of rituals and, apparently, for entertainment. While the activities of dancing are attested from time to time in the sacred spaces, those in a private context are seldom documented-although one can strongly assume they took place since these are human universals that such evidence does not exist.

It does not mean that there was no dancing in private contexts, but only that it is not documented. Thus, it is a question of the source situation-at which places, which scenes were depicted or not. This lecture is going to focus on the following questions: Where and in which context do the earliest depictions appear?

Who danced? Which movements are attested? Does anything change during the course of time? To answer these questions, first we will get a small introduction on how the dance is depicted. Then I give you a short overview about dance in ancient Egypt. We look at the costumes and the instruments played by the dancers, take a look at the context, and then we draw a conclusion.

The earliest steps

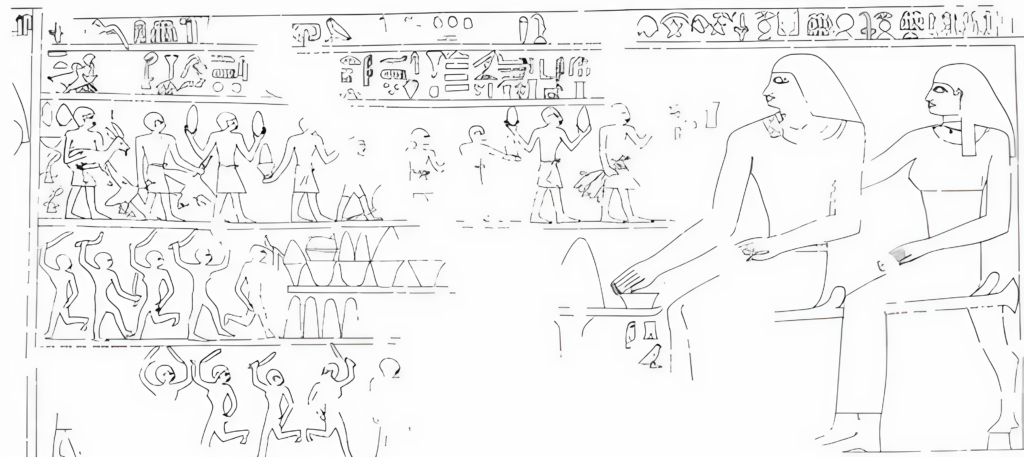

Dance in ancient Egypt present themselves as extraordinarily diverse: from static to ecstatic, to acrobatic. Whereas musicians are often instructed by chironomists this is not documented for dancers. Who are the dancers? As general performers, both men and women are attested. Those dancers who appear in an official context, be it in a procession or in a funeral, are certainly professionals.

While members of the royal family like Nefertiti and her daughters, as well as the king can be shown with a sistrum as a kind of musician, this is not attested in connection with dance.

How is dance depicted?

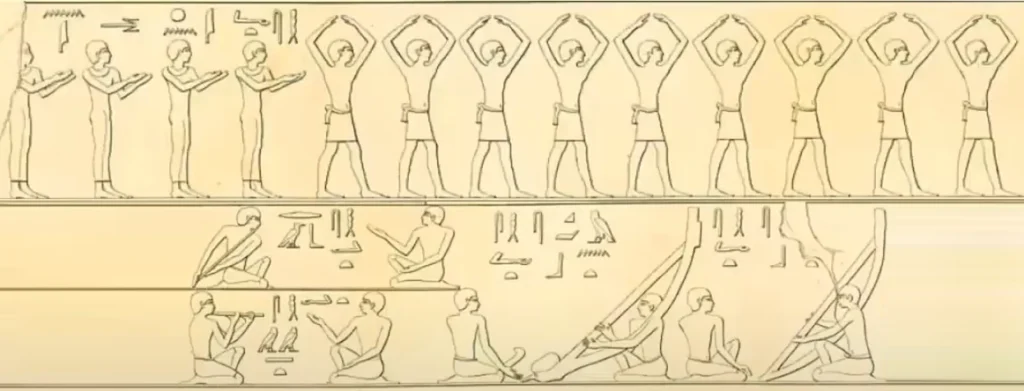

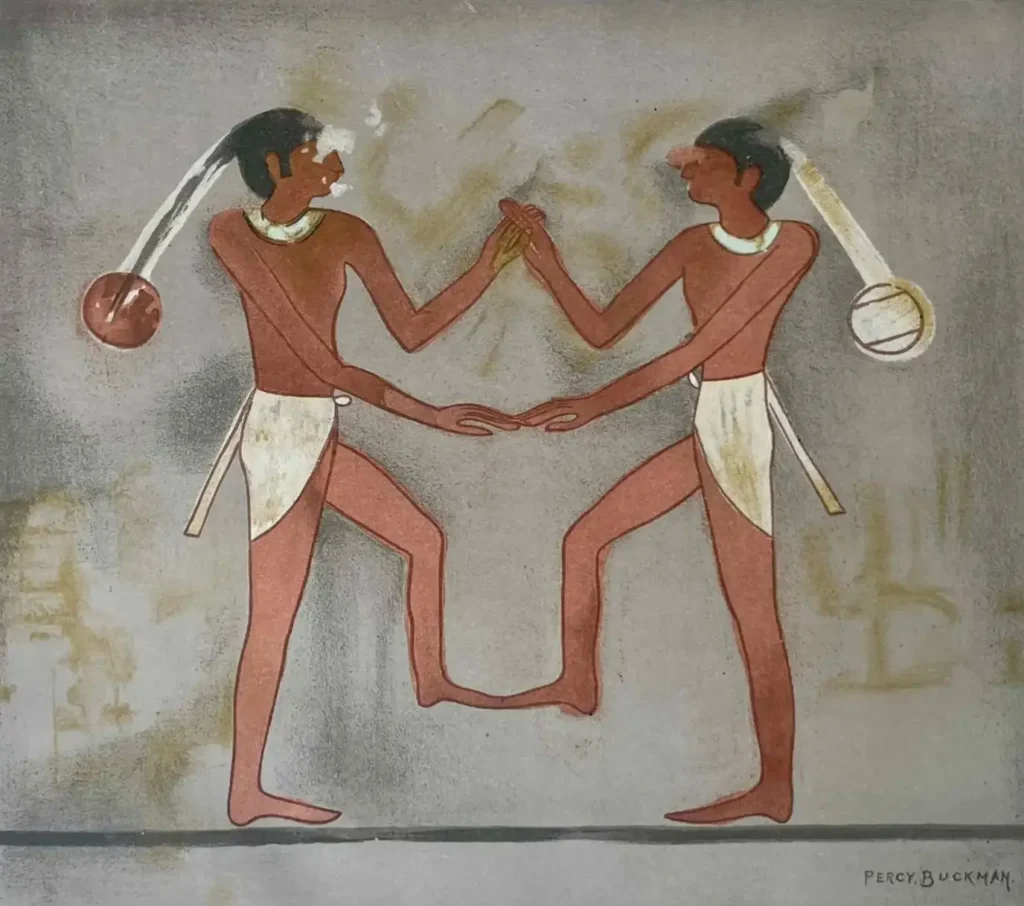

Dancers can be identified by the fact that for instance, both of their arms were raised above their heads-a usual pose since earliest times-or by other poses whereby one arm does not take necessarily the same position as the other.

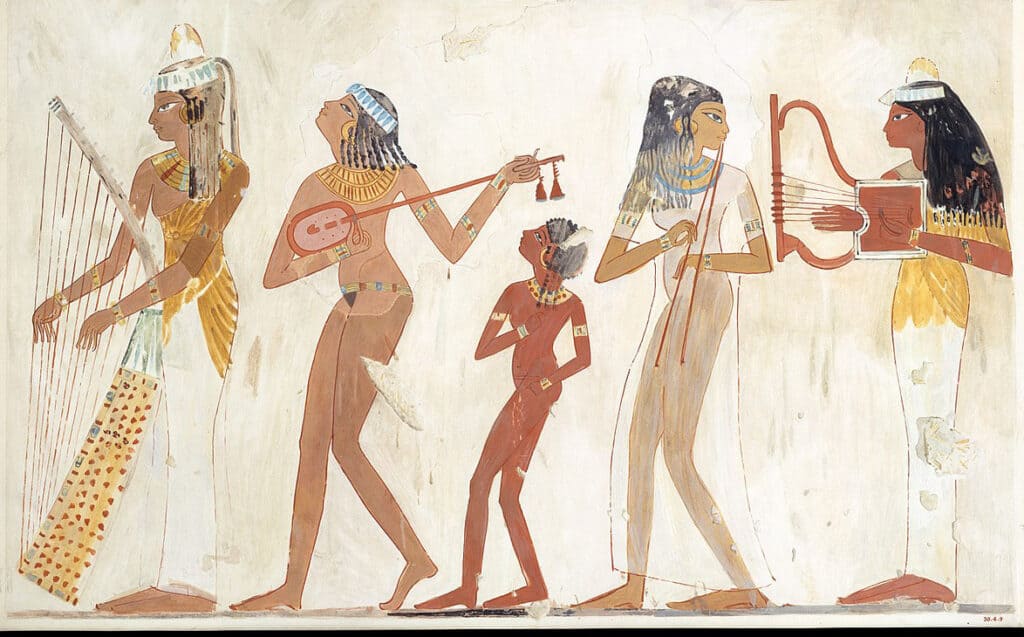

Music scene: Tomb of Khuenre, Giza, 2530 BC: Female harpist, 3 singers of the khener group, dancer

Moreover, their feet are more or less raised above the ground. Sometimes this is hardly noticeable, as in the tomb of Kena Moon, and you have to look very closely to see that she is moving.

Tomb of Kenamun, Thebes, TT 93, reign of Amenhotep II (1428-1397 BC)

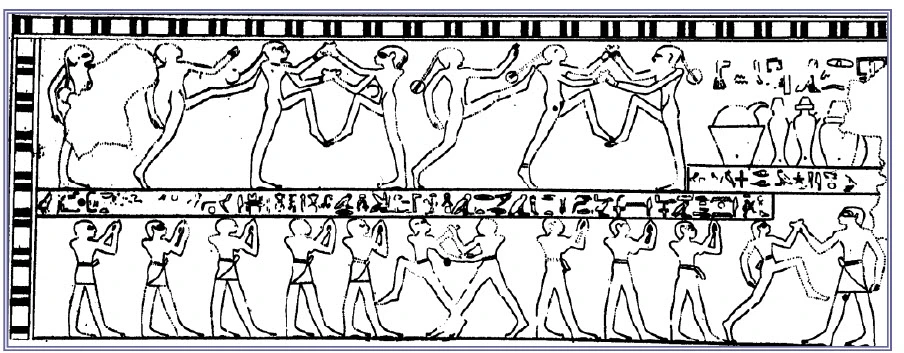

The biggest ensemble is depicted in the tomb of limerj in Giza (G 6020, Dynasty 5, ca. 2450 BC)

21 actors including dancers

4 hand clapping persons giving the rhythm for the whole ensemble including 9 dancers.

Rustling clothes, barefoot dancers, the sounds that the listeners produce

Tomb of Kaichenet and Chentkaus in Hemamiye (ca. 2500 BC): nine women with clappers

The Dancers: Who were they?

It is in these ancient scenes that we have seen groups of dancers, both men and women, commonly depicted in pairs or in small ensembles. Some of these dancers were professionals and part of the royal court or religious processions, while others were ordinary people, immortalized in tomb art.

While for most musical scenes, one finds definite indications of the chironomists who guided the musicians, there are no such guides for the dancers—their movements, though synchronized, were likely spontaneous, following tradition, emotion, and the demands of the ritual at hand.

One of the most striking images from Kaichenet’s tomb shows dancers in different postures, some with arms high in the air, others with very light footsteps. It was a reminder that there was room, even in ancient Egypt, for diversity in the way one danced—whether to please the gods or to entertain the living.

Ecstatic, Acrobatic, and Static: The Movements of Ancient Dance

The dance of ancient Egypt ranged from the static to the ecstatic to the acrobatic. Early tomb depictions show slow, deliberate movements, the dancers raising their arms in a common gesture that has been passed through millennia.

But this was not the only dance form. Gradually, it developed acrobatic elements as well: backflips, high kicks, and even aerial leaps are shown on temple walls. In the tomb of Kheroev, we find a series of dancers with heads up, heads down, arms up, arms down; this seems to be some kind of choreographed rhythm, almost hypnotic in character, seemingly to express to the gods with bodily movements themselves.

A Dance with No Instruments: The Silence of Transition

One thing which is truly interesting to learn about Egyptian dance is the fact that it is silent. Dancers, without one musical instrument to accompany them, in a place where life and death meet at perhaps one of the largest crossroads—the tomb of Debaqeni. There is no flute, no drum, no lute. Only the moving human body accompanied by song and the rhythm of breath.

In this silence, the dance is much more than just a performance—it is a prayer. This lack of instruments screams out, and it does so by pointing to the deeply personal nature of these performances. It was the body itself that would communicate with the gods, and it was the body that would help the soul cross into the afterlife.

Conclusion: Dancing Away Death?

Can one dance away death? No, but certainly one can make the journey easier. To the ancient Egyptians, the dance was not a show to be performed for people in the audience. The dance was an integral part of the most important moments of life. It helped guide the dead through the perilous journey to the afterlife so that safe passage into eternity was ensured.

It was a means of connecting with something greater-than-the-self, be those gods, the dead, or the living. And it was in that moment, really, that the body moved through space, the lines began to blur between life and death. To dance in Ancient Egypt was to exist in an in-between, to reach beyond the physical world into that of the divine.